As the 200th anniversary of the campaign comes to a close, we have one last guest post by Alice Shepperson. Alice has summed up the career of Marshal Murat, paying particular attention to the attributes that made him a good (or not so good) choice to take over command of the destroyed Grande Armée when Napoleon left it to return to France in December of 1812.

—

On leaving the Grande Armée in December 1812, Napoleon appointed his brother-in-law, Joachim Murat as commander-in-chief. The King of Naples would desert just six weeks later, leaving Prince Eugène to attempt to rescue the army’s desperate situation. How was Napoleon so mistaken?

Joachim Murat was the son of a country innkeeper. His family intended him for the church and sent him to study theology in Toulouse. Given his flamboyant, energetic nature, extreme vanity and powerful, athletic build, Joachim’s relations should not have been surprised when at the age of twenty he ran off with a passing cavalry regiment. Joachim enlisted as a private, but with the coming of the Revolution, officer rank came within the grasp of commoners – especially well educated, loudly republican commoners like Murat.

Lieutenant Murat came to Napoleon’s attention on 13 of Vendemiaire 1795. He happened to be in temporary command of the 21st Chasseurs when Bonaparte ordered them to seize the 40 guns of the National Guard on the Place de Sablons. Thus it was Murat who provided Napoleon with the “whiff of grapeshot”, that saved the Convention and made him a national hero. Murat was rewarded with an appointment as Napoleon’s aide-de-camp.

In Italy, Egypt and soon throughout Europe, Murat proved himself a fearless and effective cavalry commander, renowned for his reckless bravery and desire to lead every charge in person. His tactics involved quick movement and rapid strikes, exploiting any mistakes by the enemy. At the battle of Aboukir, his attack was so swift that he overtook the Turkish commander, who in resisting capture, shot Murat through the jaw. Refusing to go to hospital, he bandaged up his face and carried on with the battle.

Murat’s relationship with Napoleon was complex. He was instrumental in Napoleon’s rise to power, securing the cavalry’s support for his coup of Brumaire 1799. Soon after, Murat secured Napoleon’s consent to marry his favourite sister, Caroline. Now part of the family, Murat took an active part in the squabbling, intrigues and backstabbing habitual to the Bonapartes, mostly aimed at ensuring each sibling got their fair share of the palaces, titles and territories dispensed by Napoleon. Josephine complained to Madame de Remusat that the Murats “…kept up their own influence by exciting the Consul to passing fancies and promoting his secret intrigues.” Though, Napoleon often found his family excessively grasping, Murat remained indispensible as both a commander and an ally.

However, when Napoleon gave Murat the crown of Naples in 1808, their relationship began to sour. Murat was a proud man and felt that like any monarch he should have free rein in his own kingdom, while Napoleon treated him as a mere French military governor, constantly questioning his domestic policy, dictating the movements of French troops in Naples and generally interfering. This caused constant chaffing between the two men.

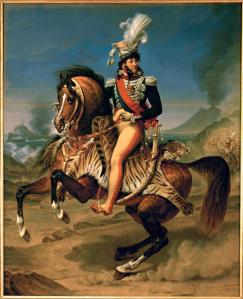

Being crowned also inflated the dandy in Murat. His personally designed battle costume for the Russian campaign consisted of long yellow leather boots, crimson and gold fur-lined breeches, blue tunic with gold lace, red velvet pelisse and a tricorn hat decorated with ostrich feathers and diamonds. This was set off by a diamond encrusted sabre and gold spurs. A less conspicuously brave man would have been ridiculed.

By 1812, Murat and Napoleon appeared to have buried their differences and the “First Horseman of Europe” once again served with distinction, taking a leading role at Borodino and almost every other engagement. As commander of the cavalry, his responsibilities were especially onerous. On the advance, the cavalry were employed in chasing the Russian rearguard, and throughout the campaign Cossack raids made constant patrols necessary, which Napoleon insisted should be large enough to prevent detachments being isolated and killed. In addition, the cavalry were expected to forage for the rest of the army and do reconnaissance. There was simply no time to feed and rest tired mounts. By the crossing of the Beresina there were only 1,800 mounted cavalrymen left.

On the 5th of December, Napoleon left the Grande Armée in the care of Murat. For several reasons, he was the natural choice: he was a king and therefore highest ranking; he was family, implying loyalty to the Empire; he was an experienced commander-in-chief who had held independent commands since 1801.

For several other reasons, Murat was a terrible choice:

Murat’s elevation to kingship, rather than binding him more tightly to the Emperor, had in fact made him less reliable. Obsessed with maintaining his new dignity, his chief concerns were now not with the army, but in Naples with Caroline, their children and his crown. When Devout reminded him that he owed his kingdom to Napoleon and to French blood, he replied, “I am as much King of Naples as Francis is Emperor of Austria and I may do as I please.”

Murat was also intrinsically ill-suited to the enormous task. As Berthier wrote, “The King of Naples is the first of men for executing the orders given by a commander-in-chief on the battlefield. The King of Naples is in every way the most incapable of acting as commander-in-chief himself.” Almost as soon as he took command, Murat asked to hand it over to Eugène, who he said was more experienced in administration. This was not strictly true, as Murat had been organising whole armies for longer, and administering his own kingdom since 1808. Napoleon put it well when he later said to Caroline, “He is a brave man on the battlefield, but feebler than a woman or a monk when the enemy is not in sight. He has no moral courage.” Murat was perfectly capable of detailed administration when the goal was victory. Without the prospect of new glories to spur him on however, he lost motivation, and lacked the inner resources to find it again.

The Russian campaign had also affected Murat deeply. He was physically and mentally exhausted, and though a veteran of many battles, was at least sick at heart, if not actually shaken. Berthier wrote in a dispatch to the Emperor in December, “The King of Naples is very unsettled in his ideas”, and recommended again that he be replaced.

The Russian campaign had also affected Murat deeply. He was physically and mentally exhausted, and though a veteran of many battles, was at least sick at heart, if not actually shaken. Berthier wrote in a dispatch to the Emperor in December, “The King of Naples is very unsettled in his ideas”, and recommended again that he be replaced.

By January 15th, Murat was pleading that he must leave the army on the grounds of ill-health, though when he did leave on the 17th, he managed to travel straight to Naples without stopping. “Not bad for a sick man!” was Eugène’s assessment.

Most importantly though, Murat had lost faith in Napoleon. After Leipzig, he abandoned the French cause to save his kingdom, only to take it up again during the Hundred Days when the allied powers looked to dethrone him. Following Waterloo he fled to Corsica, from where he tried to organise an insurrection to regain Naples. Neapolitan forces eventually captured him and he was executed by firing squad. Vane and defiant to the last, he faced his death standing and without a blindfold, shouting, “Soldiers! Do your duty! Straight to the heart but spare the face. Fire!”

—