Thank you to James Fisher for today’s post. James has been a great supporter of this blog with both information and encouragement. He has compiled a series of eyewitness accounts showing the condition of the army and the condition of the bridges at the Berezina.

—

(24th November) Condition of the ‘Grande Armée’

Sergeant Bourgogne of the French Imperial Guard related the condition of the ‘Grande Armée’

Napoleon’s Retreat from Moscow

by Adolf Northern

“…the days were short—it was not light till eight o’clock, and it was dark by four in the afternoon. This was the reason why so many unfortunate men lost their way, for it was always night when we arrived at the bivouac, and all the remains of the different corps were in terrible confusion. At all hours of the night we heard the weak, worn-out voices of new arrivals calling out ‘Fourth Corps!’ ‘First Corps!’ ‘Third Corps!’ ‘Imperial Guard!’ and then the voices of others lying down with no strength left, forcing themselves to answer, ‘Here comrades!’ They were not trying any longer to find their regiments, but simply the corps d’armée to which they had belonged, and which now included the strength of two regiments at most, where a fortnight earlier there had been thirty. No one knew anything about himself, or could mention which regiment he belonged to.”

Mikaberidze, A (2010) The Battle of the Berezina: Napoleon’s Great Escape, Campaign Chronicles (Ed. C Summerville). Pen & Sword Books Limited, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK. p. 110

(25th November) Victor’s IX Corps is United With the ‘Grande Armée’

On the March from Moscow

by Laslett John Pott

Having been unaware of the plight of the retreating ‘Grande Armée’, Marshal Victor and his troops were stunned to see, not soldiers but “a mob of tattered ghosts draped in women’s cloaks, odd pieces of carpet, or greatcoats burned full of holes, their feet wrapped in all sorts of rags… [we] stared in horror as those skeletons of soldiers went by, their gaunt, grey faces covered with disfiguring beards, without weapons, shameless, marching out of step, with lowered heads, eyes on the ground, in absolute silence, like a gang of convicts.“

General Hochberg, future Margrave of Baden added:

“I will never forget that day. I ordered my brigade to stop to observe the scene, the likes of which none of us had ever witnessed. We first saw twenty non-commissioned officers carrying flags, followed by generals, some on foot, others mounted, many of them in women’s silk-lined fur coats… The weather that day and the sun brightly shone on the scene, so painful for us to watch.”

Joseph Steinmüller observed an army “without any semblance of order or discipline… Only around the flags and eagles one could see armed men marching; the rest had no arms and covered themselves in furs and rags.“

Mikaberidze, A (2010) The Battle of the Berezina: Napoleon’s Great Escape, Campaign Chronicles (Ed. C Summerville). Pen & Sword Books Limited, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK. p.95

(26th November) Constructing The Bridges and First Crossing

General Eblé and his pontonniers [often incorrectly termed as engineers] performed amazing and heroic feats in constructing three bridges, using whatever materials were available. Several perished while undertaking the work.

Ségur relates “the rising of the waters had made the traces of the ford entirely disappear. It required the most incredible efforts on the part of our unfortunate sappers [i.e. pontonniers], who worked in the water up to their mouths, struggling against the ice carried down by the current. Some of them died of the cold or were forced under by the great blocks of ice.”

Mikaberidze, A (2010) The Battle of the Berezina: Napoleon’s Great Escape, Campaign Chronicles (Ed. C Summerville). Pen & Sword Books Limited, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK. pp. 125.

“In order to supplement the boats or skiffs missing, three small rafts were built, but the wood used for want of anything better was of such small dimensions that each raft could carry no more than ten men.

On the 26th, at eight in the morning, Napoleon gave an order that the bridges be built up. Two of them were started immediately at a distance of about six hundred feet. Meanwhile, a few horsemen swam across the river each with a voltigeur riding behind him, and some three to four thousand infantry crossed it on the rafts.

… The number of trestles being insufficient for the two bridges, and for repair, in case of accidents, their construction was continued all day. At one o’clock in the afternoon, the bridge on the right was finished; it was set apart for the infantry and cavalry only, because the boards, used to cover it, were of very poor quality, four or five layers thick.”

Anon (2010) Passage de la Beresina 26, 27, 28 et 29e Novembre 1812. First Published 1812. The Naval & Military Press Ltd., Uckfield, East Sussex. 32 pp.

While waiting his turn to cross, Fezensac of the 4th Line counted his effectives to compare them with the list that he had brought from Moscow:

“Alas! What changes had take place since then! Out of seventy officers scarcely forty remained, and of these the greater part were inefficient from either sickness or fatigue… Almost all the company cadres had been destroyed at Krasnyi, which rendered the maintenance of discipline a still more difficult matter. Of the remaining soldiers I formed two peletons, the first consisting of grenadiers and voltigeurs while the second was from the centre companies. I selected the officers to command them and ordered each of the others to take a musket and always march with me at the head of the regiment.”

Mikaberidze, A (2010) The Battle of the Berezina: Napoleon’s Great Escape, Campaign Chronicles (Ed. C Summerville). Pen & Sword Books Limited, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK. pp. 142

Having completed the bridges, one can only imagine what it would have been like to be dragged from the relative comfort of a fire to enter the freezing water once more to undertake repairs. This eyewitness account, from an anonymous source, gives us some idea.

“Instead of thick planks which were absolutely wanting, round logs fifteen to sixteen feet long, and three to four ins. diameter had to be used for flooring. The carriages crossing on this uneven and rough flooring caused the bridge to jerk all the more violently that all warnings to carriage drivers to prevent their horses from going at a trot, were mostly unheeded…

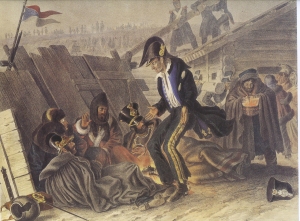

General Eblé Inspiring his Men

At eight o’clock, three trestles of the left bridge collapsed. This fatal accident distressed General Eblé. He knew how tired the bridge hands were, and he despaired of being able to gather instantly the number of men to carry out these urgent repairs rapidly enough. Fortunately, they had kept in good order. The officers and their troops and settled in their bivouacs. Only half the men were requested; but pulling away harassed, sleeping men, from around the fire, did not go without trouble.

Threats would have been fruitless, only the voice of honour and country had any meaning for these honest men. They were also stimulated by their attachment and respect for General Eblé. After working three hours, the bridge was finally repaired, and the carriages resumed their march at 11 o’clock.”

Anon (2010) Passage de la Beresina 26, 27, 28 et 29e Novembre 1812. First Published 1812. The Naval & Military Press Ltd., Uckfield, East Sussex. 32 pp.