James Fisher has again compiled a series of accounts depicting the crossing of the Berezina. These are for November 29, 1812. We also have a new contributor, Pierre Toussaint, who provided the contemporary photos of the site of the Berezina. Thank you to James and Pierre!

Contributors and Commentors are always welcome.

—

(Night of 28th/29th November) Missed opportunity by the stragglers

Site of the Cavalry and Artillery Bridge

The downstream bridge

This is the view from the right (west) bank

Photo taken November 24, 2012

Courtesy of Centre d’Etude Napoléonienne

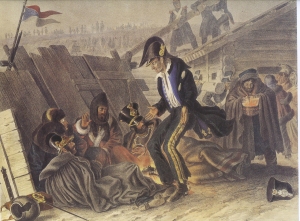

“The IX Corps left its position at about nine o’clock in the evening, after having placed posts and a rear guard to observe the enemy. They crossed the bridge in very good order, taking with them all their artillery. On the 29th, at one in the morning, the whole of the IX Corps, except a small rear-guard, had reached the right bank, and nobody was now passing on the bridges.

… However, there still remained on the left bank, some officers and soldiers either wounded or sick, servants, women, children, paying officers with their wagons, food or drink sellers, a few armed but tired men, and a crowd of isolated men with their provisions and horses. Everyone, except the wounded and sick could easily have crossed the bridges during the night, leaving behind their horses and carriages, but as soon as the enemy stopped firing the bivouac assembled in the most incredible security. General Eblé often sent word round to them, to warn them that the bridges were going to be burnt, but officers, servants, soldiers lent a deaf ear to these pressing appeals, and waited for daylight near the fires or lying in the carriages, without concern about preparing to leave.

Marshal Victor, Duke of Bellune, stayed most of the night in General Eblé’s bivouac, and failed to make this indifferent and obstinate crowd move out.”

Anon (2010) Passage de la Beresina 26, 27, 28 et 29e Novembre 1812. First Published 1812. The Naval & Military Press Ltd., Uckfield, East Sussex. 32 pp.

(29th November) Firing the Bridges

A warning to readers: this is harrowing reading.

Site of the Upstream Infantry Bridge

The Wooden Post in the center marks the location of the foot of the bridge

Photo taken November 24, 2012

Courtesy of Centre d’Etude Napoléonienne

“At five in the morning, General Eblé had several carriages set on fire, so as to prevail on the men around them; this measure seemed to be effective. At about half past six, Marshal Victor withdrew his advanced guard to cross the bridges; this action awoke the heedless. Conscious at last that they were going to fall into the hands of the enemy, they hurled themselves on to the bridges with their carriages and horses, causing a new and last obstruction.”

This was only partially successful and General Eblé and Colonel Séruzier tried to encourage more to cross the bridges before they were destroyed. Mikaberidze (2010) cites Colonel Séruzier:

View from the Right (West) bank looking East toward the Berezina and Studianka on the far bank

Photo taken November 24, 2012

Courtesy of Centre d’Etude Napoléonienne

“We knew the Russians were getting close, but I could not get the drivers of the baggage, cantinières or the vivandières to listen to reason. In vain I told them everyone would be saved if only there was a little order; that their safety depended on crossing at once, and that our troops’ salvation would depend on the bridges being broken. Only a few crossed with their light vehicles. The greater number lingered on the left bank…”

General Eblé’s dilemma at having to fire the bridges was recorded by Anon.

Monument created by Fernand Beaucour in Hommage to the French Soldiers

The Crossing Site is in the background

Photo taken November 24, 2012

Courtesy of Centre d’Etude Napoléonienne

“General Eblé having received an order to destroy the bridges at seven in the morning, he waited as long as he could to begin an operation the success of which he made secure by working out careful preparations during the night. His sensitive disposition struggled long before resolving to abandon such a large number of Frenchmen to the enemy. He waited until half-past eight before giving the orders to destroy the bridges and set them on fire.

The left bank of the Berezina became the scene of the most painful sight: men, women, children were shrieking in despair; several tried to rush across the burning bridges or threw themselves into the river in which large blocks of ice were drifting. Others ventured on the ice between the two bridges, but it gave in and engulfed them. At last, at about nine o’clock, the Cossacks arrived and captured the multitude, victim of it’s blindness.”

Mikaberidze (2010) presents Séruzier’s harrowing description of the fate of the remaining stragglers on the left bank of the Berezina:

“The Cossacks flung themselves on these people who had been left behind. They pillaged everything on the opposite bank, where there was a huge quantity of vehicles laden with immense riches. Those who were not massacred in this first charge were taken prisoner and whatever they possessed fell to the Cossacks.”

Anon (2010) Passage de la Beresina 26, 27, 28 et 29e Novembre 1812. First Published 1812. The Naval & Military Press Ltd., Uckfield, East Sussex. 32 pp.

Mikaberidze, A (2010) The Battle of the Berezina: Napoleon’s Great Escape. Campaign Chronicles (Ed. C Summerville). Pen & Sword Books Limited, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK. pp. 198–212

Tribute to the Pontonniers and General Eblé

“The pontonniers and sappers worked at the construction of the bridges with a zeal and courage beyond all praise. The pontonniers alone worked in the water; in spite of the drifting ice, they often went down to the armpits to place and hold the trestles until the beams were fixed on the caps.

Encouraged and supported by the presence of General Eblé, the pontonniers showed unlimited self sacrifice in the painful repairing of the bridges for which they were responsible. From over one hundred who went down into the water either to build of maintain the bridges, only a small number survived; the remainder died on the banks of the Berezina, or were unable to follow the Army two days after the crossing. They were never seen again.”

And General Eblé…

“As I had seen things for myself, and as the nature of my functions kept me close to the late General Eblé, I thought it my duty to supplement as much as I could the account that the General would have given of an operation he directed alone, from the beginning to the end of the crossing. The success of the construction and maintenance of the bridges was due to his active foresight, coolness and most remarkable genius of organisation. General Chasseloup paid full tribute to General Eblé. Before beginning construction of the bridges, he thus addressed his staff:-

‘I realise that the artillery has to be responsible for bridges in wartime, because its resources in staff, horses and material will still hold when other services have been exhausted. The engineers and battalion of the Danube (naval military staff) have started the campaign with a considerable artillery park of tools of all kinds, but we arrived here without a forge, nail, hammer… If the operation is successful, we will owe it to General Eblé, because he alone had the means of undertaking it. I have already told him, and I am telling you so that you might repeat to him, whatever happens.’

General Eblé placed the construction of the Berezina bridges in the forefront of the numerous services he had rendered, in the course of his long and glorious military career; during and after the crossing he repeated this declaration which carried great weight, coming from a general both modest and lucid.

When General Count de la Ribossière fell dangerously ill, General Eblé, being sick himself, was called upon to succeed him in command of the artillery at Vilna, on 9th December at a very critical time, with the energy and activity which never forsook him. He died at Königsberg on 30th December, a few days only after General La Riboissière. The great talents the virtues and integrity of the late General Eblé are well known to the French Army and to France; his name is held in great respect abroad.”

Anon (2010) Passage de la Beresina 26, 27, 28 et 29e Novembre 1812. First Published 1812. The Naval & Military Press Ltd., Uckfield, East Sussex. 32 pp.

In defense of Admiral Chichagov

Admiral Chichagov became the scapegoat for the failure of the Russian army to entrap the ‘Grande Armée’ at the Berezina, but Ivan Arnoldi of the 14th Horse Artillery Company though otherwise:

“If anyone decides to condemn Chichagov for letting the French cross the Berezina, such a charge would be misplaced since, as an eyewitness, I can testify that it was impossible to prevent it. [Chichagov] has some twenty-two thousand men under arms on the Berezina and had to defend the river over an area of over a hundred verstas (sixty-six miles), while as many enemy combatant were trying to cross it. Besides, are there any examples in history where one army desired to cross a river and someone prevented it? And it would have been even less feasible against Napoleon. Besides, we all know that Chichagov acted based on instructions received from Prince Kutusov and intelligence supplied by Count Wittgenstein, both of whom focussed their attention on the enemy crossing below Borisov and advised [Chichagov] to guard the river in the direction of Bobruisk…”

Mikaberidze, A (2012) Russian Eyewitness Accounts of the Campaign of 1812. Frontline Books (an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd), Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK. p. 237–238.

(28th–29th November) Berezina Aftermath

A warning to readers: this is harrowing reading.

Alexey Martos an engineer in Chichagov’s Army of the Danube (Third Western Army) describes the scene around the Berezina:

“Imagine a wide sinuous river covered as far as our eyes could see with human corpses; some were just beginning to freeze. Here was the empire of death in all its horror… The first thing that caught our eye was a woman who had fallen through the ice and had frozen in; one of her arms was cut off and hung loosely, with her other arm she held a suckling baby. The little thing had wound itself around its mother’s neck; the woman was still alive, she was staring at a man who had fallen through the ice but was frozen to death; between them on the ice, another dead child was lying…“

From Rochechouart, a French emigré officer serving as Chichagov’s aide de camp:

“…we saw the heaped up dead bodies of men, women and even children, soldiers of all arms, and of all nationalities, frozen, suffocated by the crush of fugitives, or mown down by Russian grapeshot; horses, carriages, cannon, caissons, wagons, abandoned. It is impossible to imagine a more appalling scene that the two broken bridges with the river frozen to its lowest depth. Immense treasures lay scattered over the region of death; peasants and Cossacks prowled around these fragments of bodies, carrying off whatever was most precious…. Both sides of the road were strewn with bodies, frozen in every attitude, or with men dying of cold, hunger, and fatigue, with their clothing in rags; they begged us to take them prisoners, and enumerated all the things they could do. We were assailed with cries: ‘Monsieur, take me with you, I can cook,’ or ‘I am a valet,’ or ‘a hairdresser,’ ‘for the love of God give me a morsel of bread, and any rags to cover me.’

Mikaberidze, A (2012) Russian Eyewitness Accounts of the Campaign of 1812. Frontline Books (an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd), Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK. p. 248 & 251.