On the morning of November 14, 1812, Napoleon and the Imperial Guard left Smolensk to resume the march west. Faber du Faur painted scenes from the next day and included the following narratives.

Between Korythnia and Krasnoi, 15 November

by Faber du Faur

Between Korythnia and Krasnoi, 15 November

“At five o’clock in the morning of 14 November, Imperial Headquarters and the Imperial Guard left Smolensk. Four hours later what remained of the 25th Division followed. there were just a couple of hundred combatants left in its ranks, although a brigade of 200 men remained behind to form part of the rearguard under Marshal Ney. We also had four guns and a confused crowd of thousands of unarmed and strangely dressed fugitives, numbers of horses and all kinds of transport. No sooner had we passed through the city’s gates than our losses began to mount; one of our gun carriages collapsed and we had to abandon the piece.”

“We dragged ourselves through deep snow, leaving traces of our passage in our wake. We made our way painfully as far as Korythnia, which we reached at nightfall, and we spent the night there. On the 15th we resumed our march towards Krasnoi. Towards noon we heard the noise of explosions; at first we took this to be the noise of caissons being destroyed, but it soon became apparent that it was the noise of cannon. We soon learned that it was the Russians attacking the Imperial Guard, for, now, we too suffered the same fate. Suddenly, through the snow, we saw a huge cloud of Cossacks flood on to the road ahead. Simultaneously, masses of infantry, cavalry and artillery appeared on our left. When they were no more than 4,500 paces from us they opened fire, sending a murderous discharge of round shot and grape against us. These were [Mikhail] Miloradovich‘s 20,000 Russians, and they had occupied Krasnoi in order to cut our retreat.”

—

Faur’s next entry has the same name and date as the first:

Between Korythnia and Krasoi, 15 November

by Faber du Faur

Between Korythnia and Krasnoi, 15 November

“We advanced, benefiting from the cover afforded by some pine trees that lined the road, and, despite our enfeebled state, fired back with our three guns. We were only able to get off a couple of shots before our pieces were silenced by the overwhelming fire of the enemy artillery. Now we prepared ourselves to fight our way through the enemy barring our way and link up with the Imperial Guard. We buried our guns so that they would not fall into the hands of the Cossacks, formed ourselves up into a column, with the armed men to the fore, and advanced. The Russians did not wait to resist our attack but moved out of the way, whilst Miloradovich’s men were content to shadow us on our left and bring their artillery to bear against us. Of course, Miloradovich could have captured every last one of us with even a tenth of his troops. Eventually we arrived at Krasnoi, having sustained some loss but having come through the enemy.”

—

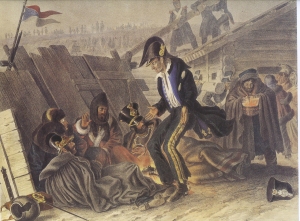

Napoleon had ordered his Corps to leave Smolensk at one day intervals and on the 15th, Prince Eugène’s IV Corps was scheduled to leave. The non-walking wounded of the Corps were gathered into one area and given some food, but then it was time for the rest of the Corps to leave. Adjutant-Major Césare de Laugier of the Italian Guardia d’Ornore described the scene that followed. “[Those being left behind] clenched their fists in despair, flung their arms round our legs, sobbed, screamed, clung to us, begged us to find them some means of transport: ‘For pity sake don’t leave us to the Cossacks, to be burnt alive, be butchered as soon as they come in. Comrades, comrades, friends, for pity sake take us with you!’ We go off with heavy hearts. Whereupon these unfortunates roll on the ground, lashing about as if possessed.”

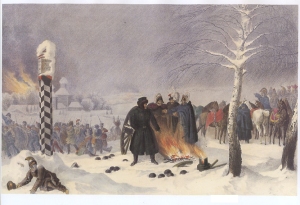

Back on the road, things are not any better as Laugier continues, “Here and there, dying horses, weapons, all kinds of effects, pillaged trunks, eviscerated packs are showing us the road followed by those ahead of us. We also see trees at whose foot men have tried to light a fire; and around their trunks, transformed into funerary monuments, the victims have expired after futile efforts to get warm. The wagoners are using the corpses, numerous at every step, to pave the road by filling in ditches and ruts. At first we shudder at the sight; then we get used to it. Anyone who hasn’t good horses and faithful servants with him will almost certainly never see his own country again. Far from exciting our sensibility, such horrors just harden our hearts.”

Sources:

With Napoleon in Russia: The Illustrated Memoirs of Major Faber du Faur, 1812, Edited by Jonathan North

1812: The Great Retreat Told by the Survivors, Paul Britten Austin, pp 148-149